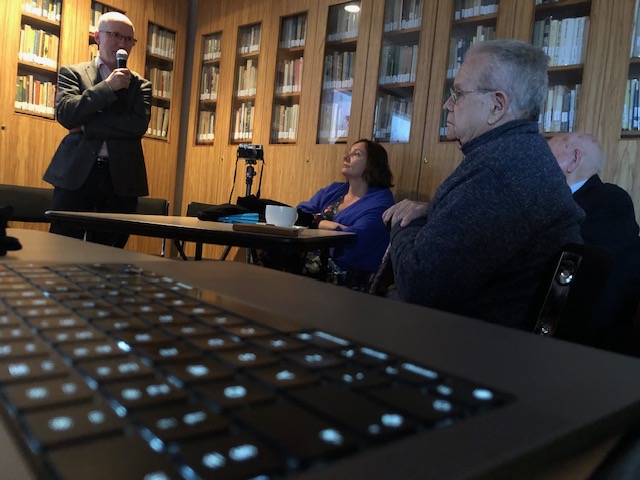

Just over a month after returning from a research expedition to New Zealand in the footsteps of Bolesław Augustis and other Sybiraks, its members shared their discoveries at a meeting at the Sybir Memorial Museum.

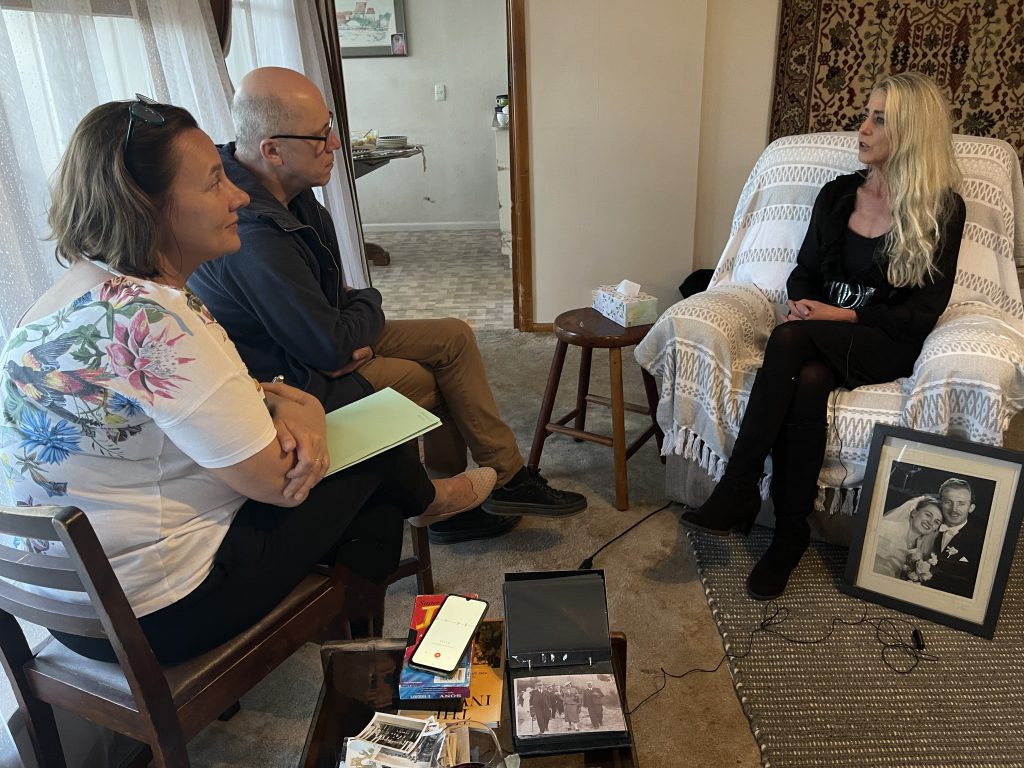

Tomasz Danilecki, PhD from the Scientific Department of the Sybir Memorial Museum and the members of the Widok Cultural Education Association — Urszula and Grzegorz Dąbrowski and Rafał Siderski, PhD — went to the other hemisphere as part of the project ‘Bolesław Augustis and the Sybiraks from New Zealand. Query and digitization of selected archives’.

The project was co-financed by Polonika The National Institute of Polish Cultural Heritage Abroad and the budget of the City of Białystok. The Sybir Memorial Museum was a partner of the project.

The evening meeting at the Sybir Memorial Museum was attended by, among others: Deputy Mayor of Białystok, Przemysław Tuchliński and Head of the Culture Department of the City Hall, Anna Pieciul. Marta Szymska from Polonika the National Institute of Polish Cultural Heritage Abroad came to Białystok especially for this evening. The relatives of one of the characters of the story, Bolesław Augustis, also came.

Productive expedition to the other hemisphere

Tomasz Danilecki, PhD, as well as Urszula and Grzegorz Dąbrowski shared their impressions from the expedition and its results with the audience. As Marta Szymska emphasized, they went to New Zealand as volunteers. Their experience and accomplishment made their expedition become the main narrative axis of the documentary film that the POLONIKA Institute is preparing about the volunteer projects it finances.

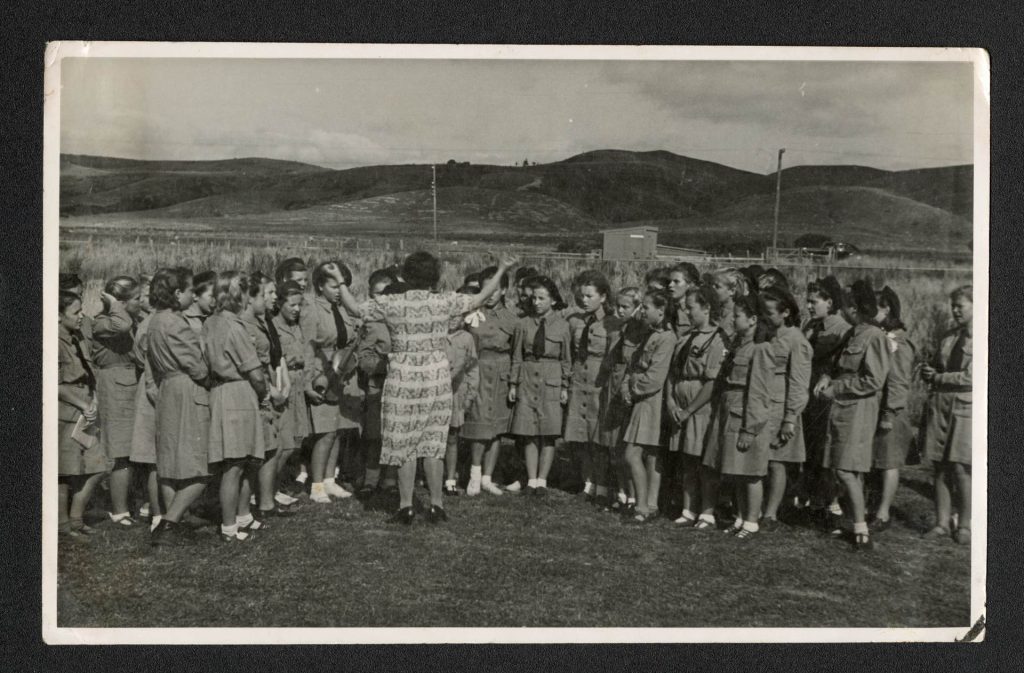

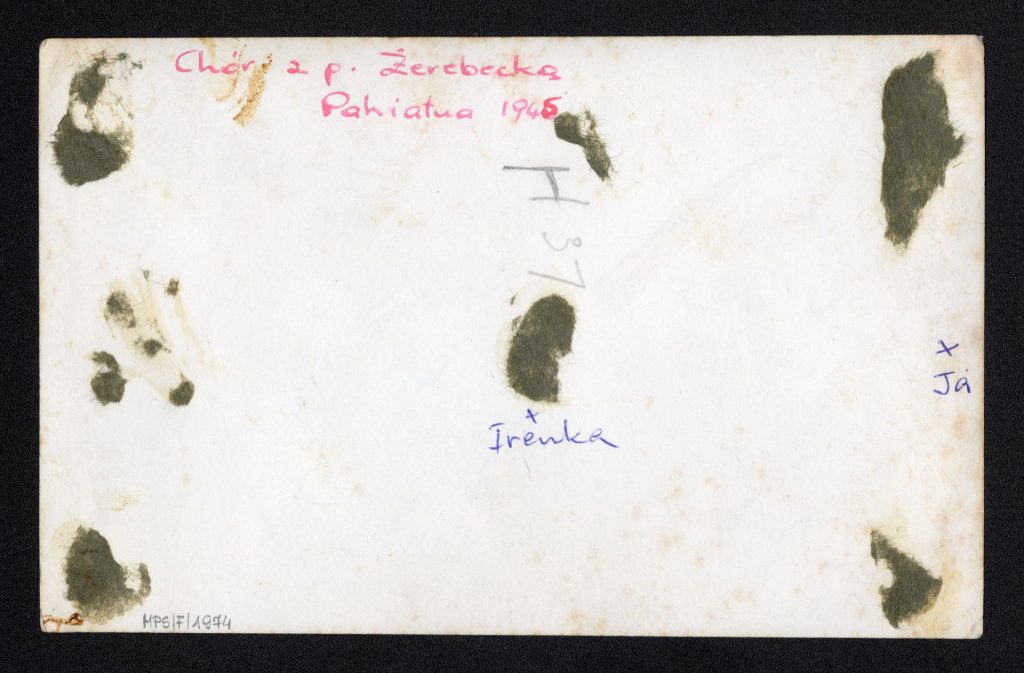

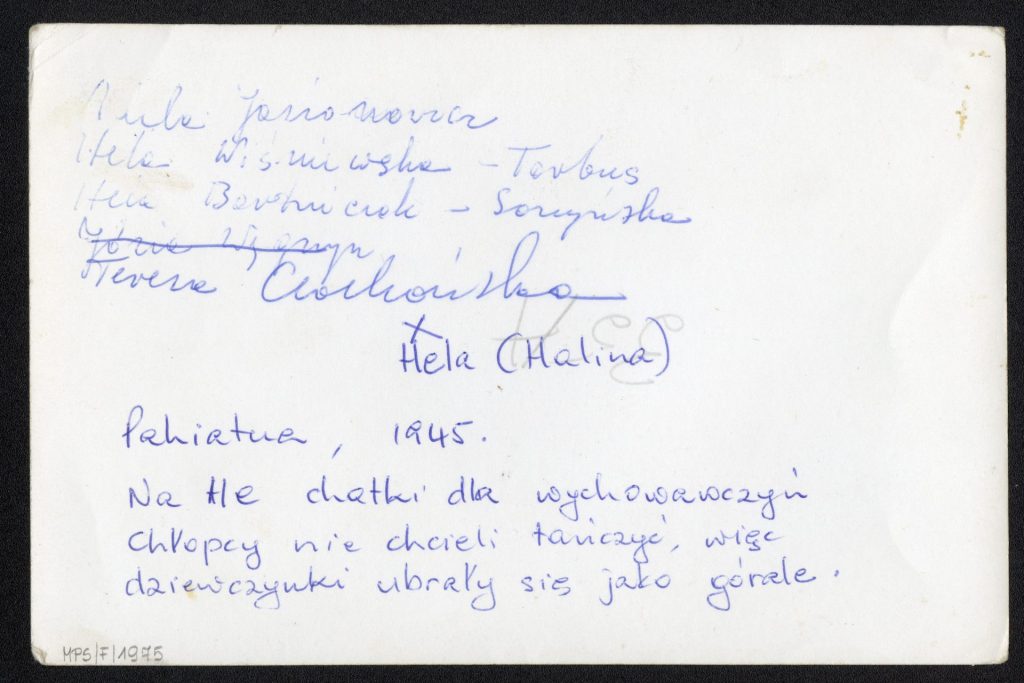

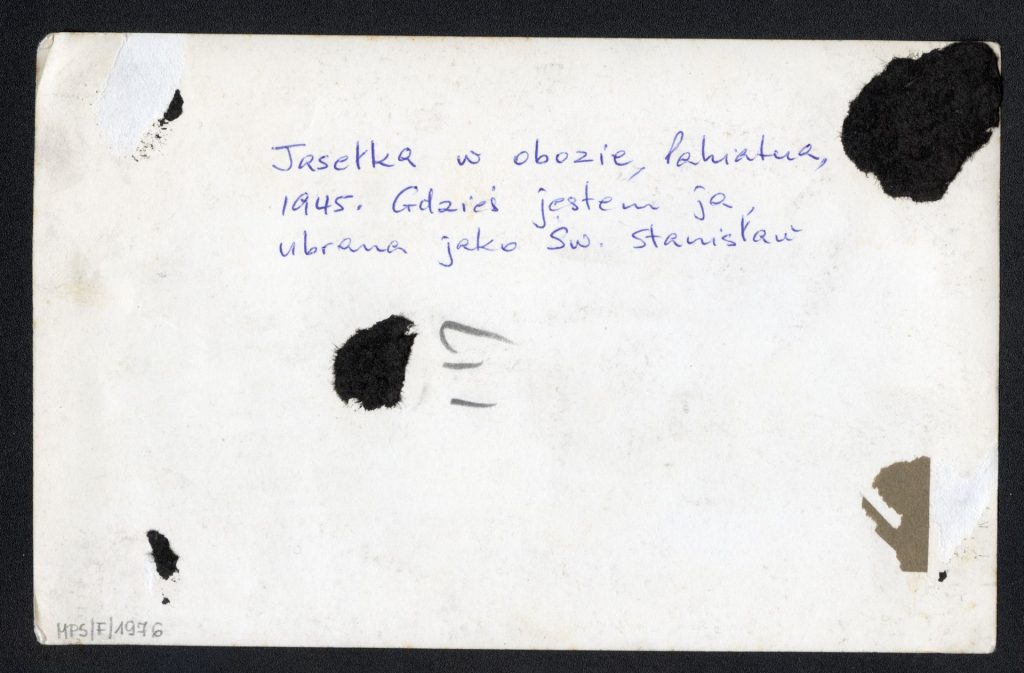

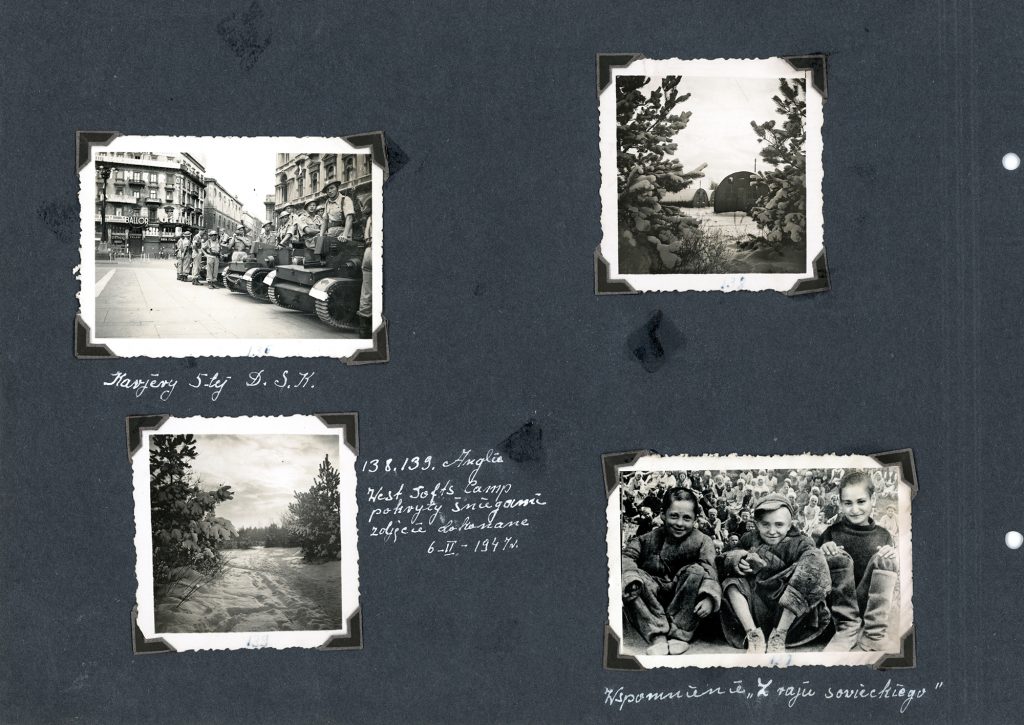

As part of the project, 12 video reports of ‘Pahiatua children’ (i.e. Polish orphans rescued from Siberia and adopted by the New Zealand authorities in 1944) and their descendants were recorded. Researchers obtained 18 pages from Bolesław Augustis’ album, containing 147 original black and white prints. Additionally, they made 217 scans of photographs from the archives of New Zealand Poles.

— It was very difficult for us to organize this trip, there was even a moment when we wondered whether it would take place — said Danilecki, PhD. — It was difficult for us to establish contact with New Zealand, it seemed to us that we were hitting a wall of silence. But once we got there, it all turned out to be an illusion, the image of our imagination was shattered. We were surrounded by great kindness, hospitality and openness.

— We planned one meeting with Polonia — three took place because the New Zealand Poles organized it for us as a surprise. We were in Auckland, Christchurch and Wellington — said the researcher. — Nina Tomaszyk, the President of the Polish Association, was very involved. Her grandmother was deported from Sokółka — he added. — Professor Krzysztof Pawlikowski, also a Polish activist, also helped us a lot.

From icy Hell to green Paradise

How did it happen that those deported by the Soviets from Poland ended up in New Zealand?

Together with Anders’ Army, 40,000 civilians were evacuated from the Soviet Union to Iran. About 18 thousand of them were children and adolescents. Thanks to British support, thousands of Polish women and children were transported to the English dominions in Africa, as well as to Lebanon, Palestine, India, Mexico and New Zealand.

— In 1943, about 1,800 children sailed to Mexico — said Danilecki, PhD. — The ship docked in Wellington for one day. They were warmly welcomed by the local people and the representatives of the authorities, including the Consul General of the Republic of Poland in Wellington, Antoni Wodzicki, and his wife Maria.

Wodzicka was friends with the wife of the Prime Minister of New Zealand, Peter Fraser. Perhaps her commitment to bringing Polish orphans influenced the decision for New Zealand to accept a group of Polish refugees who had experienced the hell of Siberia.

On October 30, 1944, 733 Polish orphans with 105 guardians and service workers arrived in Wellington. They were warmly welcomed there and then transported to the camp in Pahiatua. (You can read more about this extraordinary story on our website ‘The World of Sybir’).

— In New Zealand we saw heaven on earth. Or the dream of a mad gardener. Palm trees, cows grazing under orange trees — said Tomasz Danilecki, PhD. — Meanwhile, Stanisław Manterys, one of the Polish children rescued from Siberia and brought to New Zealand, told us: ‘None of us noticed this paradise. We all wanted to return to Poland.

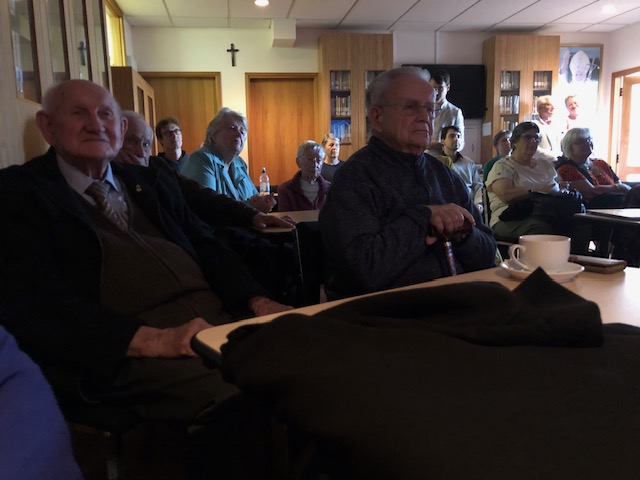

Members of the Białystok expedition had the opportunity to talk to twelve ‘Pahiatua children’. We must also add the next generations — children and grandchildren.

— There were many people at the meetings, from over 80-year-old “Pahiatua children” to their grandchildren — said Tomasz Danilecki, PhD. — When we were going to New Zealand, we were afraid that if we were another team from Poland, no one would want to talk to us. Meanwhile, the interlocutors came to us themselves. Some people traveled from far away to meet us — admitted the historian.

Polish hospitality on Antipodes

During the meetings with New Zealand Polonia, our employee talked about the Sybir Memorial Museum and how Białystok remembers Sybiraks.

— I don’t want it to sound immodestly, but the speech always ended with an ovation. Poles in New Zealand are very interested in this, they are happy that someone wants to talk to them and record their stories. Each meeting extended into several hours of discussions and conversations — said Danilecki. — Here in Poland, we remember that Sybiraks could not talk about their experience for years. The situation was different there. They could speak, but there were no listeners — emphasized Danilecki, PhD.

— We heard from them: ‘We were not believed’ — he said. — We also talked to the next generation, now adults, who regret not asking their father or mother about their Siberian experience. 58-year-old Paul drove several hundred kilometers to tell us about his father. He is very upset that he did not ask questions about Siberia when his father was still alive…

Danilecki, PhD and Mr. and Mrs. Dąbrowski’s interlocutors shared very moving stories. — Bernard Mazur talked about his father. He has only one photograph left of his parents, but he did not know which of the people in the photo were his mother and father…

Many of the children who arrived in Pahiatua were so young so little did they know of their life before deportation. They didn’t know who they were or who their parents were. — Alina Zioło was 18 months old when she was deported. She did not remember that she had siblings. In Iran, she was taken to hospital and there, her older sister accidentally recognized her: ‘This is our Alinka!’ — reported Tomasz Danilecki.

Kazimierz Zając was deported when he was 2,5 years old. He remembered that he was in the same room with his dead mother. Zbigniew Popławski remembered the moment of deportation only because after Soviet officers entered the house, his grandmother died — she had a heart attack.

— Most of them spoke to us in English. They admitted that they lost their native language around the time they were in high school — Danilecki, PhD reported. — Words associated with the strongest emotions remain in their memory: ‘mommy’, ‘grandpa’. They used them in their statements — said the historian who recorded the accounts of Sybiraks and their descendants.

Some people return to Polishness after many years! — Bronia Brooks decided to renew her knowledge of Polish language retired. When we came to her, there was a book for learning Polish on the table — added Tomasz Danilecki.

New Zealand discovers Augustis the photographer

What surprised New Zealand Poles were the stories of Urszula and Grzegorz Dąbrowski about Bolesław Augustis. He lived among them, but they did not know him as a photographer. ‘We didn’t know that our father was famous’ — Bolesław’s sons, Zbigniew and Stanisław, told researchers who came to New Zealand.

Many inhabitants of Białystok know this pre-war photographer thanks to Grzegorz Dąbrowski. When in 2004, a group of children found old photos and negatives on one of the abandoned properties on Bema Street, the news about the finding happily reached Dąbrowski, photographer and photojournalist. Since then, for almost 20 years, he has been devoting his time in order to preserve the legacy of Bolesław Augustis. It all has developed into a large project, including not only the publication of two albums of photographs, but also exhibitions, a website and a program for digitizing old photos and recording the stories associated with them.

Urszula Dąbrowska presented the history of the Augustis family during a meeting at the Sybir Memorial Museum. They probably came from the January exiles and originally used the surname Augustowicz. The photographer’s father was born in 1879 in Riga. Bolesław in 1912, already in Novosibirsk, where the family escaped from tsarist persecution. The Augustis family had an estate in Novonikolayevsk by the Kamenka River.

— In the preserved photograph showing these buildings there is an annotation: ‘They left on April 24, 1932’ — said Urszula Dąbrowska. — They reached Białystok on May 6, 1932. They stayed with Halina Świderska, activist of the Association of Siberian Deportees. Later they lived at different addresses, for the longest time on Spacerowa Street, today’s Kościelna Street.

— Bolesław started working in a photographic studio at Kościuszki Square, at Neuhüttler, resident of Krakow who initiated the so-called ‘street photos’ in Białystok, i.e. photos taken on the street — explained Grzegorz Dąbrowski. In 1935, Augustis already had his own plant on Kilińskiego Street, ‘Christian Photographic Studio Polonia-Film’. — He was a hard worker, when on Sunday people went for a walk to the park next to the Drama Theatre or to the newly established Planty Park, he was waiting for them with the camera — said Dąbrowski.

There were left thousands of photos by Augustis, many of them are the images of Białystok residents taken on the city streets.

Click here to see the gallery of photos by Bolesław Augustis on albom.pl

After the Soviets had entered Poland, the Augustis family experienced a tragedy. Jan, the photographer’s father, was arrested by the NKVD. His fate remains unknown to this day.

— In February 1940, the rest of the family was arrested, Bolesław and his siblings — explained Urszula Dąbrowska. As her husband said, most likely then their mother entered Bolesław’s factory on Kilińskiego Street and took out photographs, negatives, and maybe also some equipment. — Everything was hidden in an outbuilding on Bema Street, and the Leica camera was kept at home. After 1989, she sent it to New Zealand. There is a photo of Bolesław from those years, with this Leica camera around his neck — said Dąbrowski.

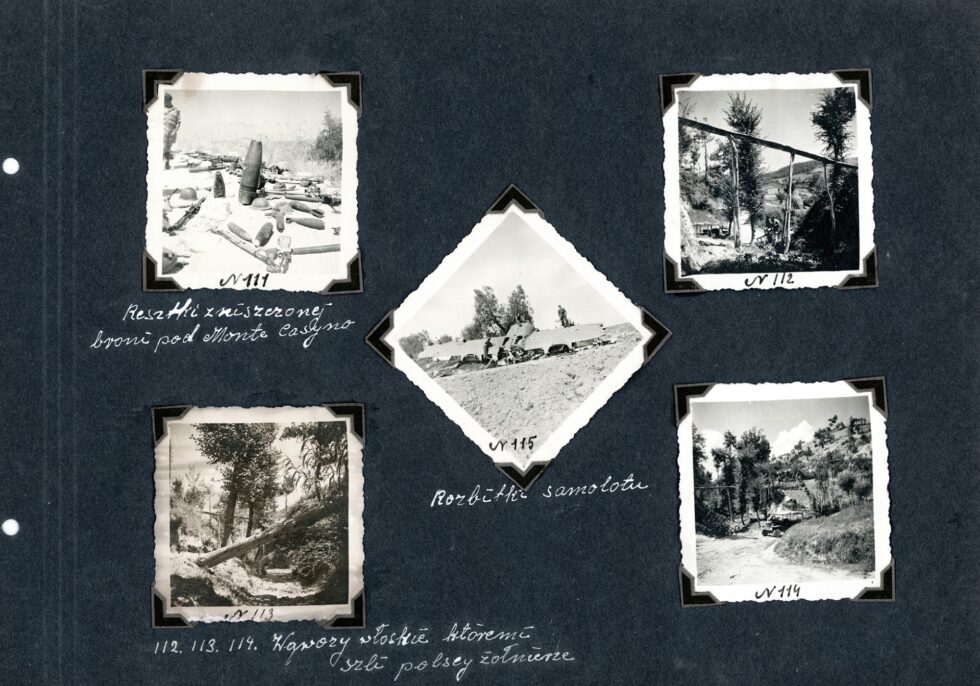

Bolesław ends up in a labor camp in the Komi Republic. After the Sikorski-Majski agreement, he is released and wants to join Anders’ Army. On the way to the mobilization point, he is captured near the city of Ukhta and again works as a slave for several months. He finally manages to reach Totskoye. In the ranks of the Polish Armed Forces, he goes through Iraq and Palestine to Italy, where he fights at Monte Cassino.

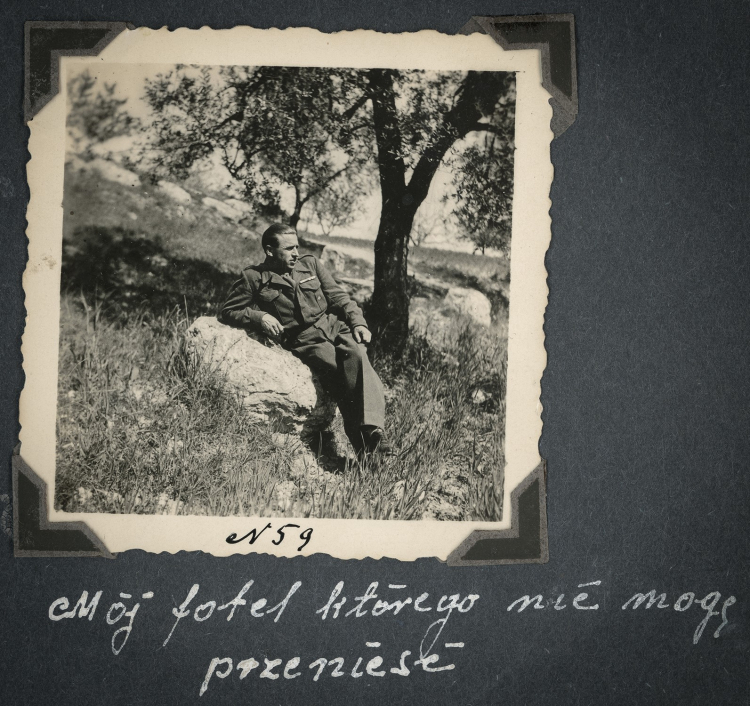

— He takes photos in Italy. There are photos similar to those from Białystok, for example girls standing on tree branches — says Grzegorz Dąbrowski, showing the audience a photo with the caption ‘Italian women on a tree peeling mulberry’.

Augustis reaches Scotland with the rest of the soldiers. There he is demobilized. He decides not to return to Poland ruled by communists. — His friends from the army, the Zazulak brothers set him up with their sister, Maria, who is in New Zealand. She was one of Pahiatua children — adds Urszula Dąbrowska. — They wrote to her that he was a good, brave bachelor. Bolesław and Maria begin to correspond and finally in one of the letters Bolesław proposes and sends a wedding ring. In 1946, he boarded the ship Rangitoto and ended up in Wellington six weeks later.

— The wedding took place one month later. It was probably a happy marriage — says Urszula Dąbrowska. Maria and Bolesław had two sons — Staszek and Zbyszek.

— Bolesław tried to return to being a photographer — said Dąbrowska. — However, he did not succeed in this new place. In New Zealand, it was not easy to quickly gain the trust of the locals. Therefore, together with the Zazulak family clan (Maria had numerous siblings), Bolesław founded a construction company. They learn to build wooden buildings according to the local method. Over time, the Augustowicz family — Bolesław in New Zealand returned to the original form of the surname — built their own house near Auckland. They work for the Polish community, help build the Polish House, which brings together the cultural and social life of the Polish community, and Zbyszek and Staszek go to a Polish weekend school.

Bolesław Augustis died in 1995. There were left negatives and family albums. Some of them were destroyed in the flood that hit Auckland in 2022.

When researchers from Białystok arrive in 2023, Zbyszek and Staszek rediscover their father. ‘He didn’t talk about Siberia, but he recalled his life in Białystok. He said that those were his happiest years’ — Grzegorz Dąbrowski recounts the words of Bolesław’s sons.

Augustis in the collection of the Sybir Memorial Museum

Impressed by the story, that Białystok remembers its photographer, the Augustowicz brothers bring the remains of the family album. These are 18 black cards, each with several black and white photos. Some made in Italy, others in New Zealand. Grzegorz Dąbrowski draws attention to the artistic level of many portraits. There are landscapes, images of animals, and even John Paul II on the TV screen.

The album by Augustis was handed over by Urszula and Grzegorz Dąbrowski to the Director of the Sybir Memorial Museum, Professor Wojciech Śleszyński. — It was the will of Zbigniew and Stanisław Augustowicz that it would be included in the collection of the Sybir Memorial Museum — they noted.

— I promise that soon, after maintenance procedures, these photographs will be scanned and placed in our collection provided online — announced the Director of the Museum.

— We also received from Bolesław’s sons over 20 rolls of films that Augustis exposed while being in Scotland. They require maintenance before scanning, so we can arrange a meeting next year where I will be able to tell and show more about it — added Dąbrowski. — The next year will be the 20th anniversary of the discovery of Augustis’s photographs — he said to Vice-President Tuchliński, who was present in the room. — Maybe this is a good opportunity to commemorate him in the city space?