The event was another in the “Museum Academy” series, organized for teachers and educators who with the help of the Sybir Memorial Museum and based on the materials we share, popularize knowledge about deportations both during school history, geography or Polish language lessons and also as part of various educational projects.

We are supported in this mission by various institutions, including the Teacher Education Center in Bialystok. In the case of this meeting, the Regional Directorate of State Forests in Bialystok joined the initiative. It was no coincidence as it was about the fate of foresters and forest settlers affected by Soviet repression.

The event was attended by representatives of different institutions – along with prof. Wojciech Sleszynski, director of the Sybir Memorial Museum, Andrzej Jozef Nowak, director of the Regional Directorate of State Forests in Bialystok and Ryszard Chodyniecki, director of the Teacher Education Center. There were also present the head of the Historical Research Office of the Institute of National Remembrance in Bialystok, the press officer of the Bialystok Directorate of the State Forests Jarosław Krawczyk and Marzena Ciruk from the Teacher Education Center. The Sybiraks’ community was represented by Jerzy Bołtuć, vice-president of the Bialystok Branch of the Sybiraks’ Association. There were also many young people from the Bialystok uniformed high school.

– We are symbolically going back to February 10, when the first mass deportation action took place in the areas occupied by the Soviets – said professor Wojciech Sleszynski. Whole families were deported. At that time, a collective responsibility was applied, because what an enemy of the system small children could be, he indicated. – A large part of those deported in the February action are foresters from our areas.

– The years of communism led to devastation of historical memory – emphasized the director of the Teacher Education Center, Ryszard Chodyniecki. – Now we are working together on regaining the memory map its shape and shows reality. The foresters were the Polish intelligentsia. The goal of the Soviets was to purge so that the Polish nation would have no future, we are regaining it – he said.

The spokesperson of the Regional Directorate of State Forests in Bialystok, Jarosław Krawczyk, emphasized the educational mission of the State Forests: – We have been prepared for generations to pass on knowledge and work with young people. This is an important aspect of our work.

In his lecture, prepared on the basis of materials provided by PhD Ewa Pirożnikow from the Institute of Forest Sciences of the Bialystok University of Technology, Jarosław Krawczyk presented a pattern according to which the fate of Polish foresters deported by the Soviets was arranged.

Foresters have been intensively trained militarily since the early 1930s, when international tensions were rising. – The Forest Military Organization was organized, many foresters participated in its training – explained the speaker.

When the Soviets entered the eastern lands of the II Polish Republic, they took over full documentation together with the resources of the State Forests including personal files of employees. On their basis, they could prepare a list of people to be deported. Of course, they also robbed the forests.

– What the Soviets did in the Bialowieza Forest was an economic cataclysm – emphasized Krawczyk. There were no properly trained people in their administration. There was a threefold increase in timber harvesting compared to previous assumptions.

On February 10, 1940, the Soviets carried out the first mass deportation action in the territories they occupied. The deportees included foresters and their families. They even went to the furthest corners of the Soviet Union – some traveled as long as three months to reach the shores of the East (Japanese) Sea. Most of them, due to the knowledge of forest management, went to work in taiga felling. It was extremely hard work, which was combined with malnutrition, high standards and difficult everyday life conditions. A certain chance for the “spiecperesielency” were parcels assigned to some people, where they could grow potatoes or rutabaga. – First, however, it was necessary to clear the forest on these parcels – emphasized Krawczyk.

The presentation of an employee of the State Forests, in addition to moving archival photos and fragments of memories, contained interesting materials about how foresters used their knowledge of the forest and its resources to ensure the survival of themselves and their families.

Wild edible plants were collected. “In that terrible spring of 1940, we ate pigweed and nettles. Mom cooked them as spinach,” recalled Jan Rębisz, who was mentioned in the presentation. – Wild garlic, or bird cherry, helped maintain the body’s immunity – the speaker said. The supplement to the diet and the source of vitamins were wild fruits collected in the forest: bilberries, blueberries, raspberries. In addition, birch sap in the spring and cedar nuts appearing in many memories, i.e. seeds from Siberian pine cones. – Mushrooms were probably widely available, but you can’t eat them for a long time, the body stops taking this heavy food – explained the forester.

The settlers tried to diversify their diet by catching fish and small birds and taking eggs from the nests. They also caught squirrels, hamsters and hares.

The fate of foresters coincides with the experiences of many other deportees, including representatives of other social and professional groups. Many of them managed to leave the Soviet Union with the Anders’ Army.

– The generation of foresters who were deported to the Soviet Union during World War II left behind the memory of the extraordinary achievements of people in conditions that devastated people – Jarosław Krawczyk summed up his lecture. – I encourage you – he turned to the young people at the end – to ask in your homes, maybe you also have Sybiraks in your family, if there are photos, souvenirs. It is worth talking about it, asking grandparents if they are still alive…

PhD Piotr Popławski, Manager of the Department of Educational and Cultural Projects, in his speech presented the biography of one of the foresters deported on February 10, 1940.

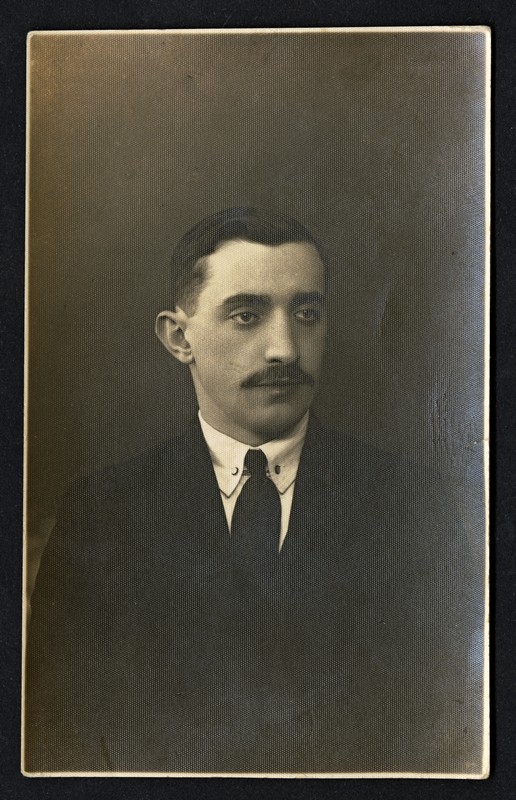

– I know that some of you will go from the Museum to Ponikla. It was from there that Henryk Prejzner and his relatives ended up in Sybir. The fate of this one family shows that each of us can find ourselves in this story. We try to show that deportations were a mass phenomenon, but not anonymous. It’s a lot of particular people’s stories.

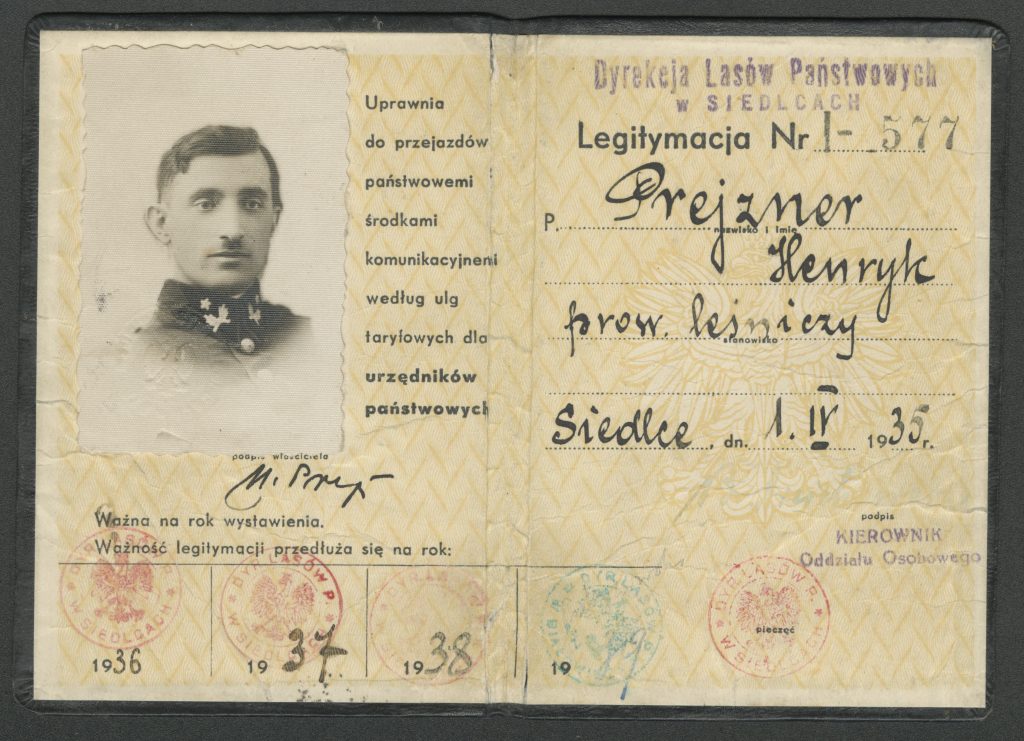

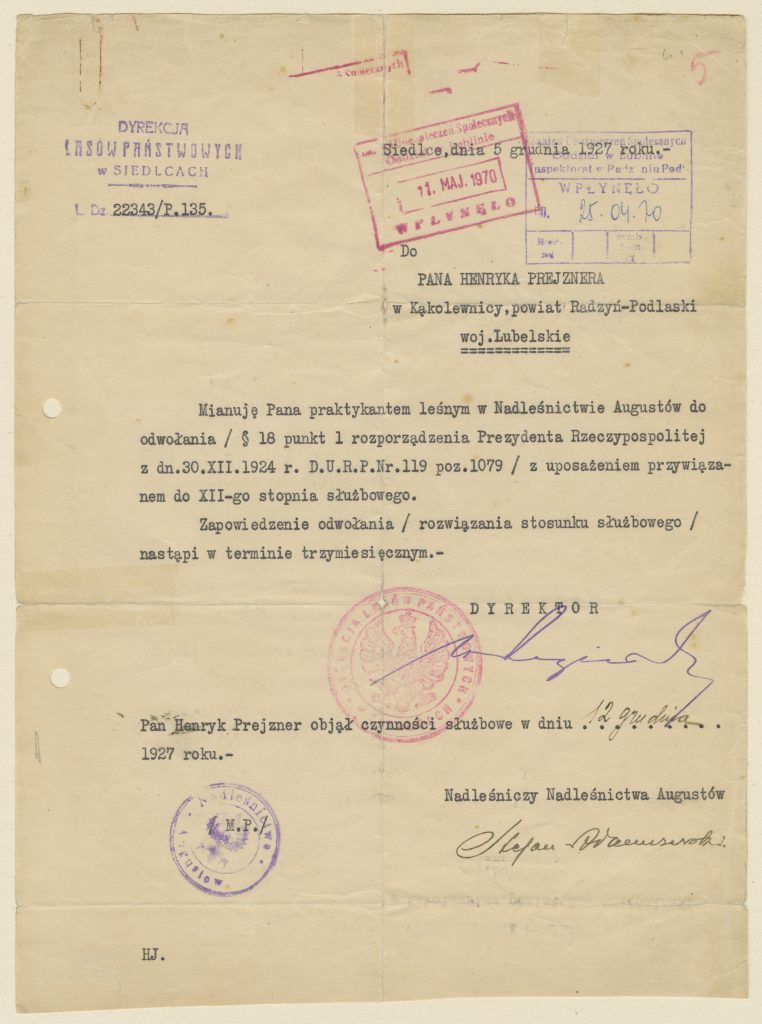

Henryk Prejzner was born on June 25, 1905 in Wojcieszkow near Radzyn Podlaski. He also graduated from high school there. Then in Zyrowice, at the State School of Agriculture and Forestry, he learned the profession of a forester. Based on the documents that are owned by the Sybir Memorial Museum, we can reconstruct his further career. He served in the Oficers’ School of Infantry Reserves in Bereza Kartuska, in Łuków and in the 34th Infantry Regiment in Biała Podlaska. He ended his service in September 1929 with the rank of platoon officer cadet and was transferred to the reserve. On January 1, 1933, he was promoted to the rank of reserve lieutenant.

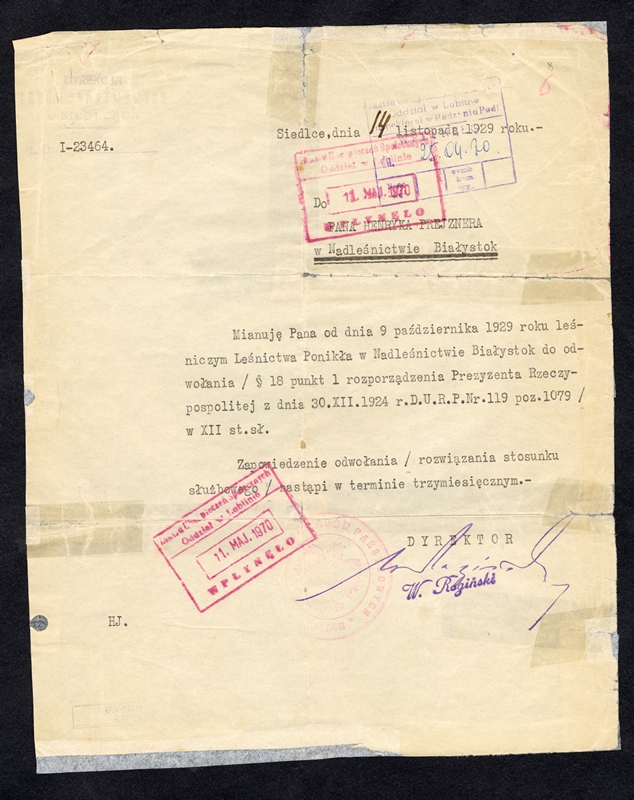

Henryk was first associated with the Augustów Forestry Inspectorate, in 1929 he was appointed a forester of the Ponikla Forestry in the Bialystok Forestry Inspectorate.

In 1932, Henryk married Maria Bakun, the sister of Michał Bakun, a forester he knew from Rybnik. The spouses live in the Ponikla forester’s lodge. Their daughter Irena and son Andrzej are born. They live a peaceful and happy life.

In August 1939, Henryk Prejzner is mobilized. His battle trail runs through Kutno, Suwałki and ends near Lviv. In October Prejzner returns to the forester’s lodge. Already under the Soviet occupation, he receives a letter from the Bialystok State Forestry Inspectorate with an order to maintain the continuity of service in the Ponikla forestry.

Meanwhile, the Soviets are secretly preparing a deportation operation. In December 1939, the Kremlin decides to deport foresters and forest guards “for security reasons” who can use firearms and know forests perfectly – thus they could become support for the Polish partisans.

On February 10, 1940, the Soviets enter the forester’s lodge in Ponikla early in the morning. Henryk is told to stand against the wall with his arms raised. Maria is ordered to wake the children and pack within an hour.

The Prejzner family, after a long and difficult journey, ends up in the deportees settlement of Złotaja Gorka in the region of Tajszet in the Irkutsk district. Henryk works there in the taiga cutting down, loading and floating trees down the river. His knowledge of forest management is noticed – after a few months, Prejzner becomes an assistant to a Russian forester and keeps the register of the harvested wood.

In 1941, the Sikorski-Mayski Agreement is signed, which provides Poles staying in the Soviet Union with an “amnesty” and the possibility of joining the Polish Armed Forces in the USSR, which was formed under the agreement. Henryk finds out about it from a newspaper secretly handed to him by a Russian worker. He decides to join the Polish army.

The Prejzner family travels to the Barnaul region, where they meet their relatives deported to Kobryn. In May 1942, Maria Prejzner and her children settled in the village of Lebiażka, and Henryk continued his journey – to Jalal-Abad, where the headquarters and staff of the 5th Infantry Division were located. The spouses are aware that this moment is a turning point. A chapter in their lives closes and a new one begins. When Henryk leaves, Maria gives him a cross on which the man cuts out the symbolic dates: “10.II.1940 SYBIR” and “1942” – is the day of deportation and the year that brought a change of fate.

Henryk makes efforts to make his wife and children leaving the Soviet Union possible with General Anders’ army. Unfortunately, the documents which should be provided by the courier are not delivered to Maria. According to family traditions, the courier sells them to another family. Since then, the fate of Henryk and his relatives has been different: he follows the trail of Anders’ Army, Maria and her children stay in the USSR.

Henryk Prejzner served in the Reserve Center of the 5th Infantry Division as a second lieutenant as the head of the quartermaster office. From 1942 he lived in Iran, Palestine and Egypt, then he ended up in Italy. However, he did not fight on the front line – he served in the rear as a supply officer, later – as a financial officer. His cartographic knowledge was appreciated, maps made by him have been preserved.

After the end of the war, most soldiers of the Polish Armed Forces remained in the West. They settled in Great Britain or decided to emigrate further. Henryk was one of those who returned to communist Poland – because of his family.

On July 18, 1947, Henryk receives a demobilization certificate. He enters a ship in Alexandria and sails to Genoa. From there, he goes by train in the direction of Poland. On November 14, he crosses the Polish-Czechoslovak border. There, Maria and his two brothers are waiting for him. Four days later they reach Radzyń Podlaski. After five years of separation, Henryk takes his children in his arms.

– Each of the individual stories is a starting point for discussing many topics – said PhD Piotr Popławski to the present teachers.

The fate of the Prejzner family can be a cause of the conversation about the Soviet occupation, deportations, living conditions in Siberia, geography and nature, about the history of the Anders’ Army, about the Polish post-war emigration environment, about communist Poland. Every Siberian story carries such richness.