The Foundation which has been operating since 2008, unites many thousand people from Polish community from all over the world. These are primarily Poles (and their descendants) with family related to the former eastern Borderlands, including many Sybiraks.

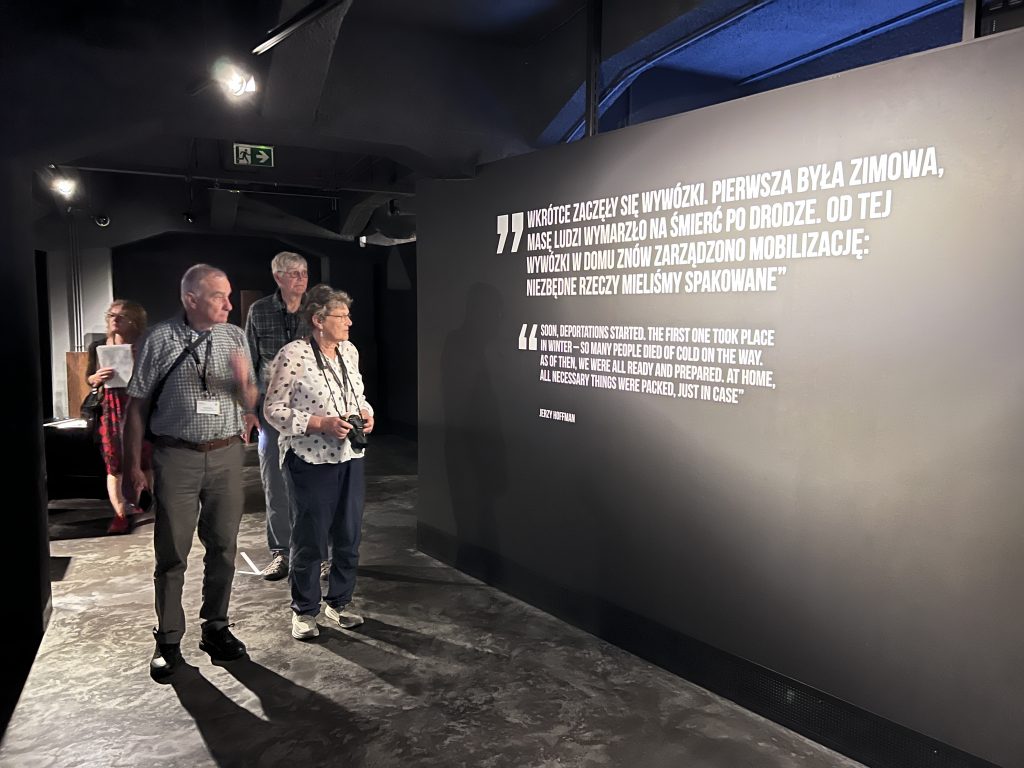

The Foundation regularly organizes the “Generations Remember” conference. In 2023, the honor of hosting representatives of the Polish community and speakers went to the Sybir Memorial Museum.

A hero of the fight for truth

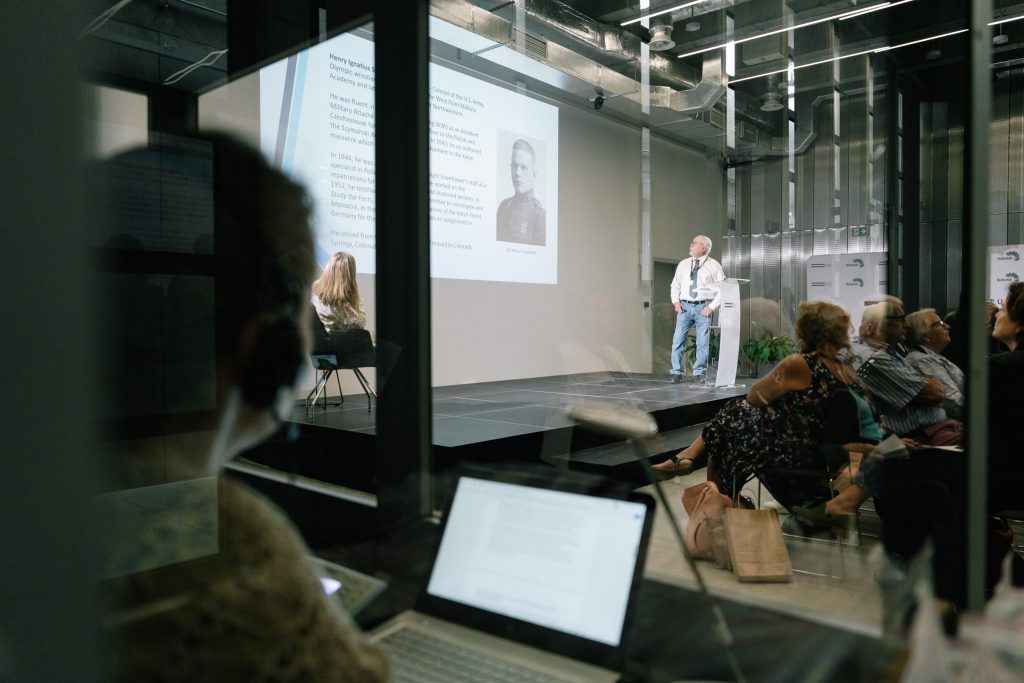

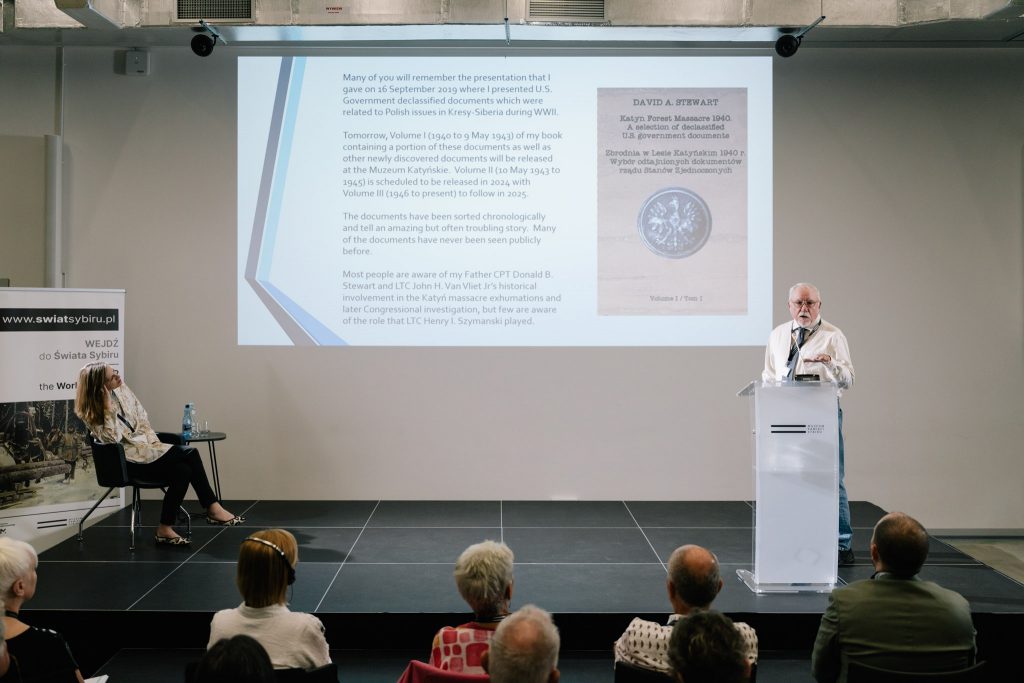

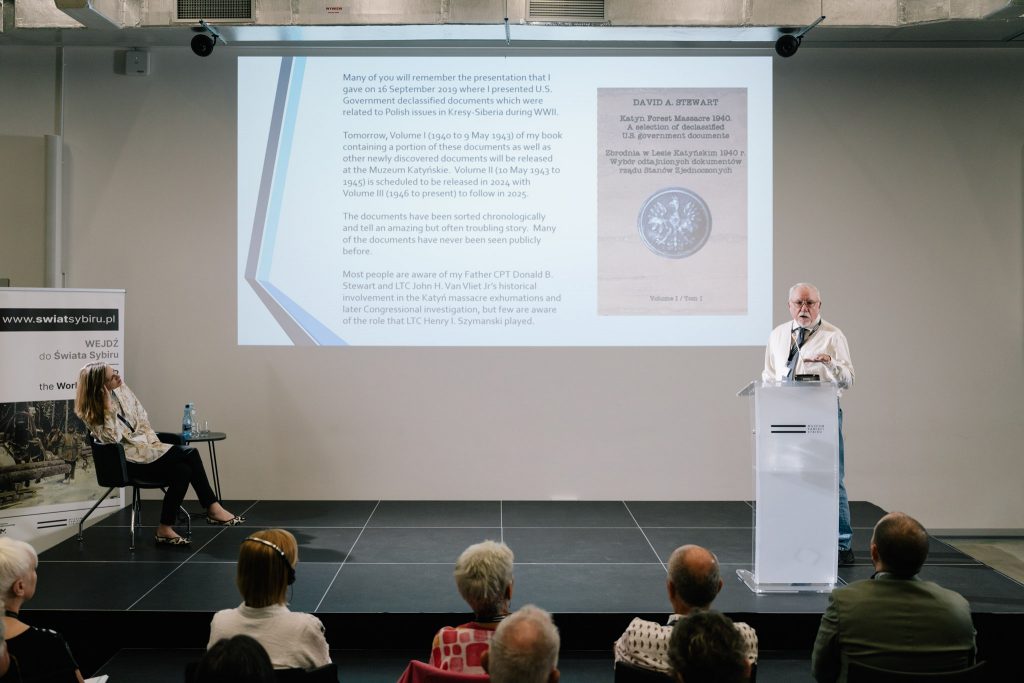

Six lectures are planned as part of the symposium. The first one was prepared by Dave Stuart from the United States, who is currently preparing a book for the Katyn Museum in Warsaw. His father, Donald B. Steward, was among the witnesses of the Katyn exhumation carried out by the Germans, and later sent encrypted messages to the United States in which he indicated the Soviets as the perpetrators of the massacre. Lieutenant John H. Van Vliet proceeded similarly.

Dave Stuart presented the results of his research on the American government’s knowledge of events in the Polish eastern borderlands during World War II, especially the Katyn Massacre. He focused mainly on the role of Lieutenant Henry I. Szymanski in finding the truth.

PodobLike Donald B. Steward and John H. Van Vliet, Henry Ignatius Szymanski (1989-1959) attended West Point Military Academy. He had Polish roots and spoke the language of his ancestors fluently. During World War II, he served as an attaché assistant in Egypt and as a liaison officer with the Polish and Czechoslovak armed forces in the Middle East. – In 1943, he co-authored a later lost report (“Szymanski Report”) on Soviet responsibility for the Katyn Massacre – explained Dave Stuart.

During his stay in Cairo, Szymanski collected relations of Poles who from the so-called Anders’ Army evacuated from the Soviet Union – where they found, among others, as a result of deportation or imprisonment in a gulag. The interlocutors reported the conditions in which they stayed in prisoner of war camps, the realities of life of deported civilians and all the information they received about the missing Polish officers.

– Shortly after the Katyn mass murder was revealed, Szymanski compiled the interviews into a 70-page document called the “Szymanski Report”. On May 29, 1943, he handed it over to American military intelligence, Stuart said.

The report consisted of a two-page introduction and nine appendices. The first testimony was Józef Czapski’s note from 1942 about missing officers.

– The report was sent to the deputy chief of staff of American intelligence (G-2), Major General George V. Strong, Szymanski’s superior. He reviewed the document and then ordered his subordinate to forward further reports on the Katyn Massacre only if they proved German participation. Then Strong marked the “Szymanski Report” as top secret and archived it.

He sent Szymanski to Italy to be a liaison officer with the 2nd Polish Corps. He went to the front line and fought, among others, at Monte Cassino – continued the speaker.

In 1944, Szymanski joined General Dwight Eisenhower’s staff as a specialist in Polish affairs. After the war, he dealt with reparations for Polish prisoners of war and the so-called “displaced persons”, staying in camps organized by the Allies – people who found themselves in the West during the war, e.g. as a result of deportation to Germany for forced labor or after being released from German concentration camps.

– In 1951, Szymanski had the opportunity to listen to a speech by Thaddeus Michael Machrowicz, a member of the House of Representatives. In a conversation with the politician, he talked about the report he prepared in 1943. Machrowicz tried to get the document, but the intelligence services were unable to find the “Szymanski Report”. This had a strong media response, because it would be the second missing report on the Katyn Massacre (after Van Vliet). Two days later, “The Washington Post” informed that the “Szymanski Report” had been found, but Annex No. 9 had been sent to Nuremberg earlier. There is no trace of Van Vliet’s report, added Dave Stuart.

In 1952, Henry I. Szymanski testified before the committee investigating the Katyn Massacre and in the same year he began intelligence work for the CIA in Germany. He retired a year later and lived in Colorado until his death.

To help our compatriots – Polish delegacies in Kazakhstan

There was another session after the break. Dmitryi Panto, PhD, an employee of the Museum of the Second World War in Gdańsk, connected with Białystok via online video conference. His lecture concerned Polish delegacies in Kazakhstan in 1941-1942. – The functioning of the delegacies depended on the current relations between the Polish government and the Soviets – explained Panto, PhD.

The network of Polish government delegacies in the Soviet Union was established after the signing of the Sikorski-Majski Agreement (which took place on July 30, 1941). – The scope of activities of delegacies included everything that consulates did, and even more, as Polish ambassador Stanisław Kot recalled – said the researcher. – The Soviet Union did not agree to open consulates under the pretext that it would not be able to ensure the safety of diplomats. In my opinion, Kot was right when he wrote that the Soviets identified the consular service with spies – he added.

Delegacies were legalized on January 8, 1942. Until mid-June, they worked efficiently to the best of their abilities.

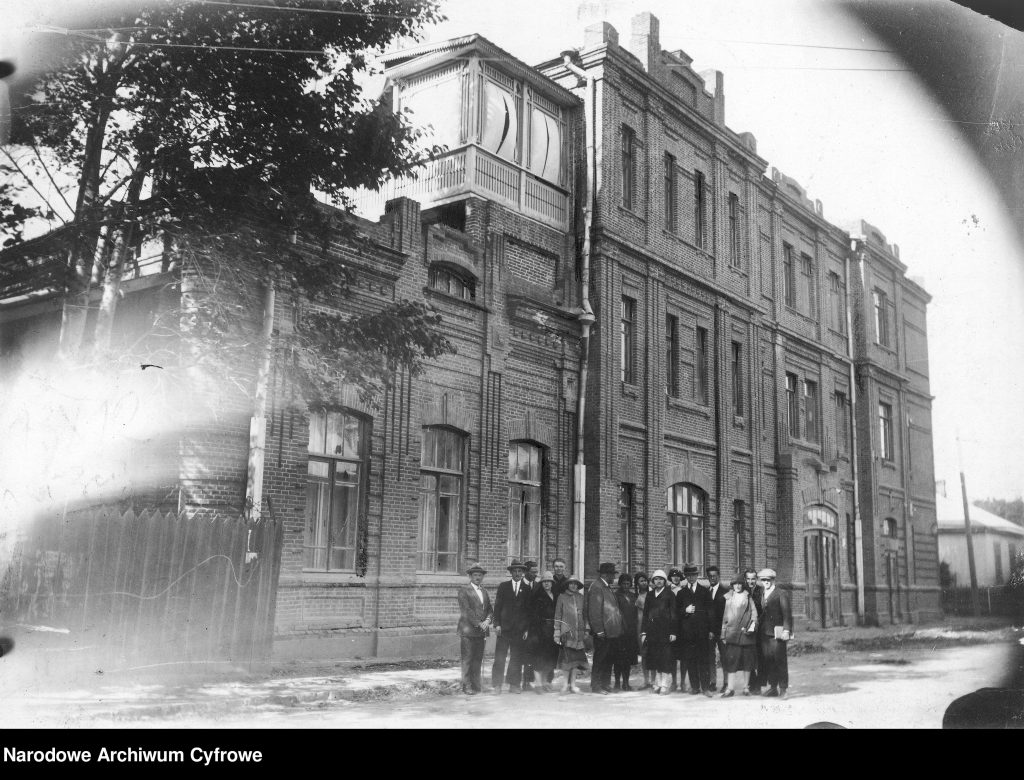

What did the delegacies do? First of all, providing help. Here, Poles staying in the USSR could obtain a Polish passport, financial assistance, receive clothes or food. – The Polish community gathered around the delegacies, sometimes such a building was called the “Polish House” – said Panto, PhD. At the delegacies there were clinics, hospitals, orphanages for children and old people’s homes, a chapel and a Polish school. Material support aids received from the Allies were stored in warehouses.

Many Poles survived thanks to delegacies, also because they provided employment. – There were jobs here, for example, for a typist or a warehouseman – explained the scientist.

According to the Polish side’s plans, a whole network of institutions was to be established. At the top of the structure there was to be the Polish embassy in Moscow, subordinated delegacies and representatives of trust in the districts, liaisons in the regions, kolkhozes and sovkhozes. The representatives of trust were to be in the field for the delegacies. Unfortunately, only 20 delegacies were established finally. There were few connectors. Many tasks rested on the shoulders of men of trust.

The Polish government wanted to provide care to as many Poles as possible and to create facilities at important transit points, including port cities – to receive help (medicines, food, clothes) from the Allies. But the Soviets did not agree to establish delegacies in the capitals of the regional republics, they had to be other cities. The exception was Almaty.

As Panto, PhD, explained, the work of the delegacies was difficult due to logistics and communication problems and obstruction by the local authorities. – Local officials were afraid to cooperate with the delegacies due to fear of being accused of spying, so they consulted each decision with the management, which took weeks – said the historian. There were also difficulties in reaching many places. A car or horse was needed. Communication was terrible. – The dispatch could take a week – said the speaker.

– At the end of July 1942, the Soviets began to close the delegacies, under the pretext that there were fewer and fewer Poles in the Soviet Union – continued Panto, PhD. Some delegates were arrested. The closure of delegacies in sea ports exposed Poles to hunger. They lost access to food warehouses.

– The arrest of delegates with diplomatic status met with opposition from the Polish government – said the historian. – Ambassador Kot filed a protest on July 9, 1942, demanding the release of the delegates and the return of documents, money and seals seized by the Soviets. Meanwhile, they accused the delegacies’ employees of spying.

– It had a disastrous impact on the fate of the deportees. The distribution of clothing, food and cash benefits has been suspended. The Soviets took over the warehouses. Many orphanages and nursing homes were left without support.

The liquidation of the delegacies was a planned action – explained Dmitryi Panto – which was completed on July 20, 1942. All delegates were subject to an NKVD investigation that lasted from July to October. A total of 770 people were arrested. Many delegacies’ employees were sentenced to gulags. 78 people were expelled from the USSR. Among them were those who returned to London. Their relations and reports are today important historical sources, available at the Sikorski Institute, the scientist emphasized.

After the NKVD operation, only the men of trust operating in the field remained, but eventually their offices were closed and they were arrested. Many of them were accused of spying and were sent to gulags.

After the discovery of the Katyn Massacre, when the USSR broke off relations with the Polish government, the Soviets took over the remaining buildings and warehouses of the delegacies. They established their own network of facilities based on the Union of Polish Patriots.

Concluding his lecture, Panto, PhD appealed to remember the employees of the delegacies, representatives of the trust and all those committed to working for their compatriots in the USSR: – Working in the delegacies required commitment and perseverance. They were heroes, they worked for the good of others for 14-16 hours every day, under the supervision of the NKVD, risking their own freedom and even their lives, emphasized Panto, PhD.

The World of Sybir portal – travels in time and space

During the third lecture, Tomasz Danilecki, PhD from the Scientific Department of the Sybir Memorial Museum presented “The World of Sybir”– a popular science portal – to the audience. This is an initiative of the Museum carried out with the support of the Juliusz Mieroszewski Dialogue Centre. Texts prepared by specialists from various science branches – history, archival science, ethnography, literature and art – presenting issues related to Sybir are regularly published here.

Podcasts – programs which can be listened in any time are an important part of the website. There are also separate sections as “Knowledge Base” with a collection of films, recordings and photographs and “Sylwetki”, introducing people related to Sybir in its broad sense.

The portal’s creators also publish here archival photos whose history (or the photographed people) is unknown. Thanks to the community that is forming around the website, it has already been possible to describe many photos and identify people and places. The portal is going to become a place for exchanging information for Sybiraks’ descendants from around the world. That’s why it is made not only in Polish but also in English language version.

Remembering, recalling, keeping silent…

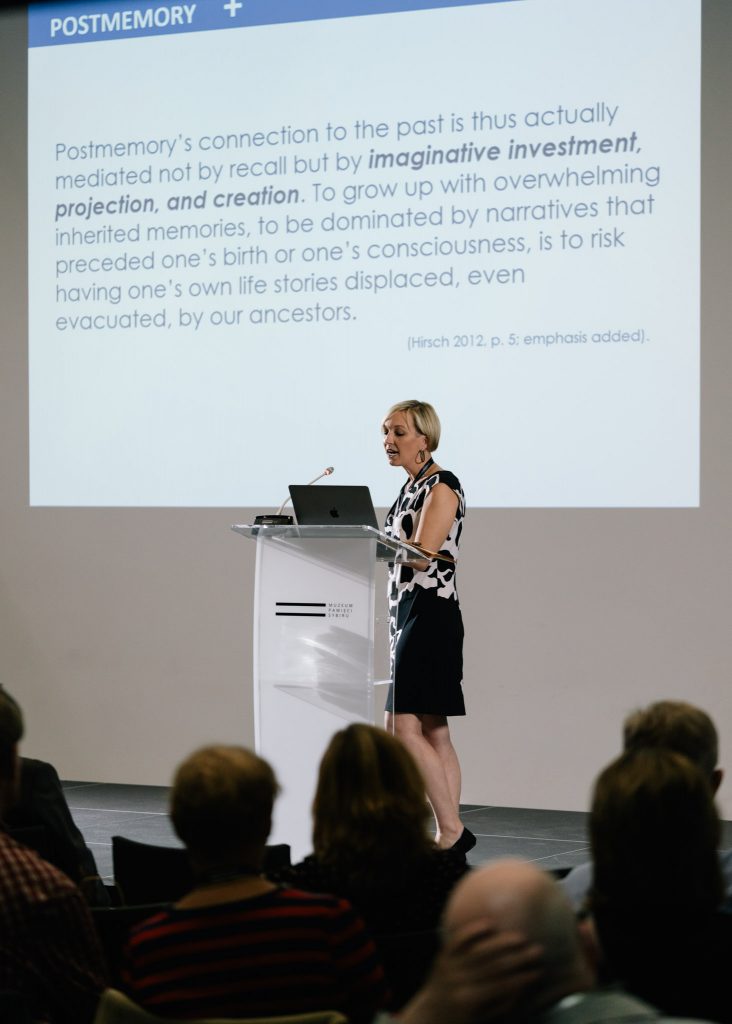

The fourth speech was a lecture by Alison Urban, PhD from the University of California, San Diego. The researcher discussed the phenomena of memory and post-memory, as well as the processes of transmitting memories between generations. “We talk so much about memory because we have so little of it left,” was the motto of the lecture, chosen from the book “Between Memory and History” by Pierre Nora.

The San Diego scientist’s areas of interest are collective memory, its intergenerational transfer and sharing.

The speaker referred to her own experience as a descendant of Sybiraks growing up in America. Although she spoke in English, she used Polish words when talking about family members: – I grew up hearing these stories told by my grandmother and aunts. So I was convinced that everyone knew about the deportations and Sybir. How surprised I was when nothing was said about it at school!

Alison Urban drew attention to how young generations absorb the memories of their parents or grandparents: – I felt that the memories of my aunts and grandmothers were mine.

The scientist devoted part of her lecture to the fourth generation and phantom memory and postmemory. There is no stories in many families, the truth about their roots has not been shared. It is caused sometimes by the physical absence of an ancestor, sometimes as a result of conscious silence. It is not always easy to find or share a family history without traumatizing either the teller or the listener.

However, memory is needed – so that we know our roots and can create our identity, but also to honor those who were condemned to forget.

– An act of memory is an act of resistance. It is a refusal to be forgotten. Because being unnoticed causes a wound… – said Urban.

– How to encourage for telling and sharing history? – the researcher asked and recalled an example from her own life. – My aunt once told me: Nobody talked until you started asking…

Polish builders of the Siberian railway

The fifth speech was a journey in time and space – Marta Czerwieniec-Ivasyk, preparing her PhD at the University of Natural Sciences and Humanities in Siedlce, presented the profiles of Polish railway workers building the Trans-Siberian Railway.

– Over 15 thousand people with Polish identity worked on the Trans-Siberian Railway. I am preparing a biographical dictionary, there are 600 names on my list – said the researcher.

– These were people who had lived in Siberia for a long time, for example, descendants of rebels, hard laborers and exiles. There were also many Polish peasants and workers who went to Siberia to work. Some officials received work orders. A large group consisted of refugees (bieżeńcy), i.e. Poles resettled during World War I, as well as former prisoners of war or soldiers who took part in the Russian-Japanese war in Manchuria and chose to settle in Siberia after the defeat of the army, Czerwieniec-Ivasyk enumerated.

The scientist presented the profiles of selected people involved in the building of the Trans-Siberian Railway.

Kazimierz Falkowski (1875-1936) was vice-president of the Directorate of the Aczyńsko-Minusińska Railway. After returning to Poland in the 1920s, he worked at the Supreme Audit Office, and in the 1930s he was director of the railway in Vilnius.

Hieronim Bejnar-Bejnarowicz, born in 1860, was the son of a post-January exile. He started working on the railway as a wagon enumerator at the Taiga station. Later he was an official of the West Siberian Railway. – There are records that he kidnapped his wife, Helena née Zaleska, from the station where she worked in the cafeteria – said the researcher with a smile. – Although everything was probably done with the lady’s consent, the records are filled with outrage that such an act was committed by an official. However, the marriage was probably happy – concluded Czerwieniec-Ivasyk.

Teofil Włostowski (1868-1930) was a socialist ideologist. From 1888 he was active in the socialist party. Arrested, he spent the years 1894-1896 in Pavilion X, and then in 1897 he was exiled to Siberia. In 1902, according to sources, he was an employee of the Transbaikal Railway in Irkutsk. After Poland regains independence, Włostowski’s wife leaves for her homeland. He stays in the Soviet Union and dies in Moscow in 1930.

Czesław Miłosz’s father, Aleksander, also appeared among Polish railway workers. He built railway bridges in Siberia. – However, years later, in his professional biography he did not write about the time spent on this work – the speaker noted.

The part of Czerwieniec-Ivasyk’s lecture on Harbin (aka Charbin) was extremely interesting. – Today it is the sixth largest Chinese city – she said. – And it was founded by a Pole and for years it was a center of Polish culture.

Engineer Adam Szydłowski (1860-1916). Delegated by the management of the East China Railway, which was just being built, he chose this point on the map of Manchuria, on the Sungari River, as the administrative center for the railway. It was supposed to connect southern Siberia with the port of Vladivostok on the Sea of Japan. Construction began in 1897. A year later, Szydłowski bought the old distillery and initiated the development of the city on his land. In 1903, the first train passed through this land.

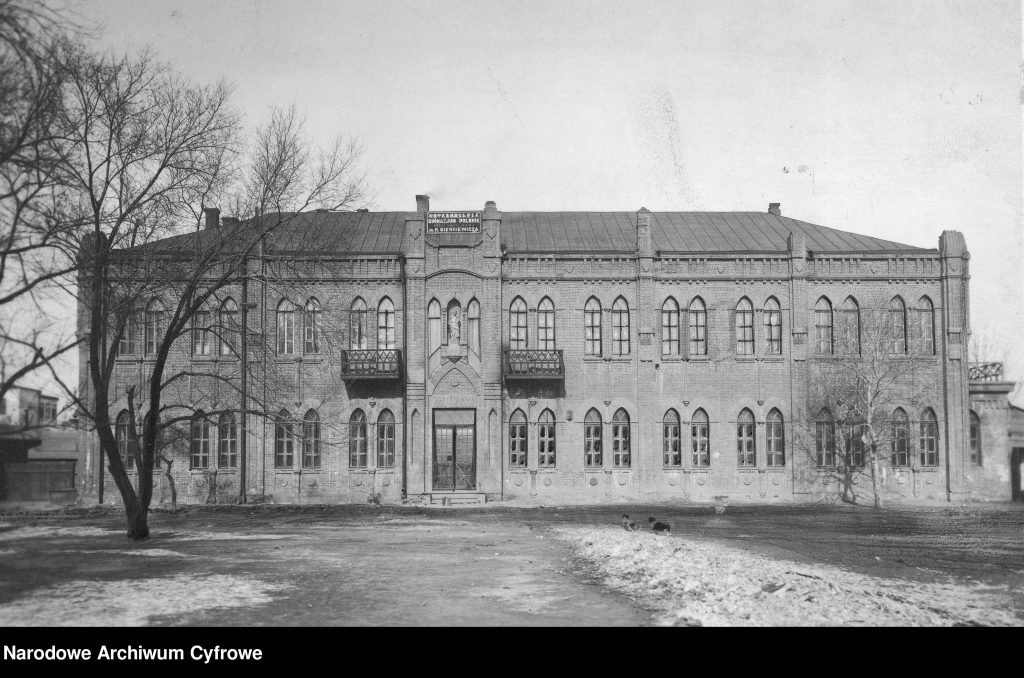

– The station building, no longer existing, was a replica of the station in Siedlce – the researcher pointed to the photo. – This is a project by architect Ignacy Cytowicz.

– There were two Roman Catholic parishes and Polish schools in Harbin, Poles created associations, scouts and many enterprises here – she said.

– There are still two Harbin associations operating in Poland, in Świebodzice and Szczecin – added Marta Czerwieniec-Ivasyk.

At the end of her lecture, the researcher invited everyone to visit her website, which is a database of historical information about Polish railway workers – www.kolejarze-online.pl.

A virtual museum for the whole world

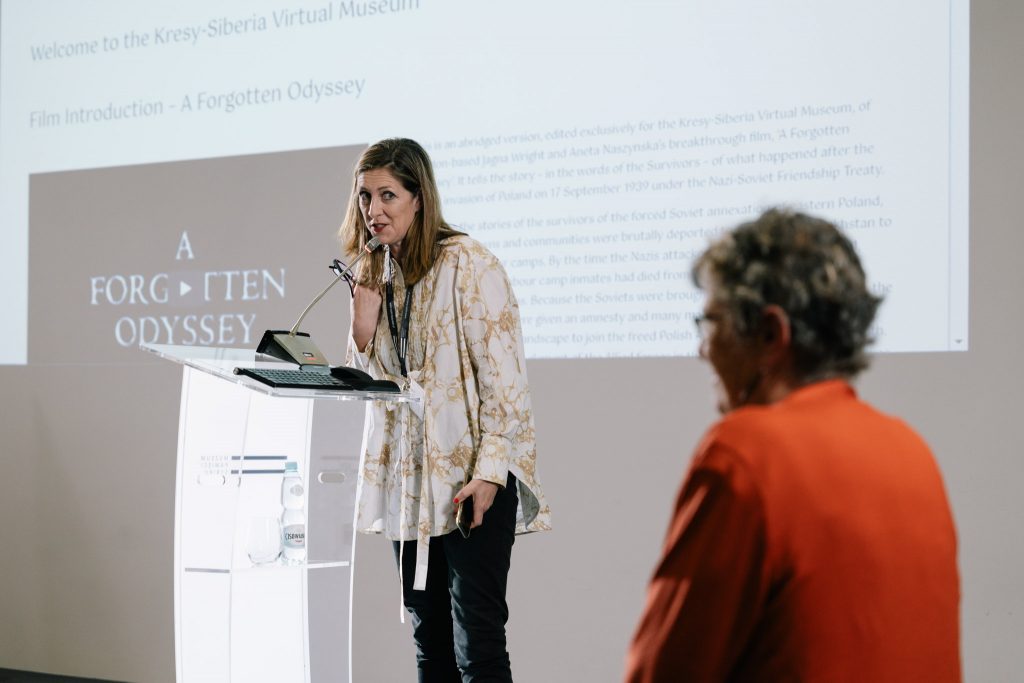

The conference ended with the presentation of the Kresy-Siberia virtual museum run by the Kresy-Siberia Foundation. Irena Lowe from New Zealand and Anna Pacewicz from Australia took the audience on a virtual walk.

This portal presents the history of Polish Sybir in Polish and English language versions. It provides a large database, including a list of the repressed (Wall of Tribute), as well as a large supply of photos and documents. In the “Testimonies” tab you can find hundreds of written stories and recorded statements of historical witnesses.

Members of the community around the Kresy-Siberia Foundation spent three more days in Białystok. They visited the permanent exhibition of the Sybir Memorial Museum and took part in the events of the World Sybirak Day – promotion of the SYBIR monograph, a theatre performance and the city celebrations on September 17th.