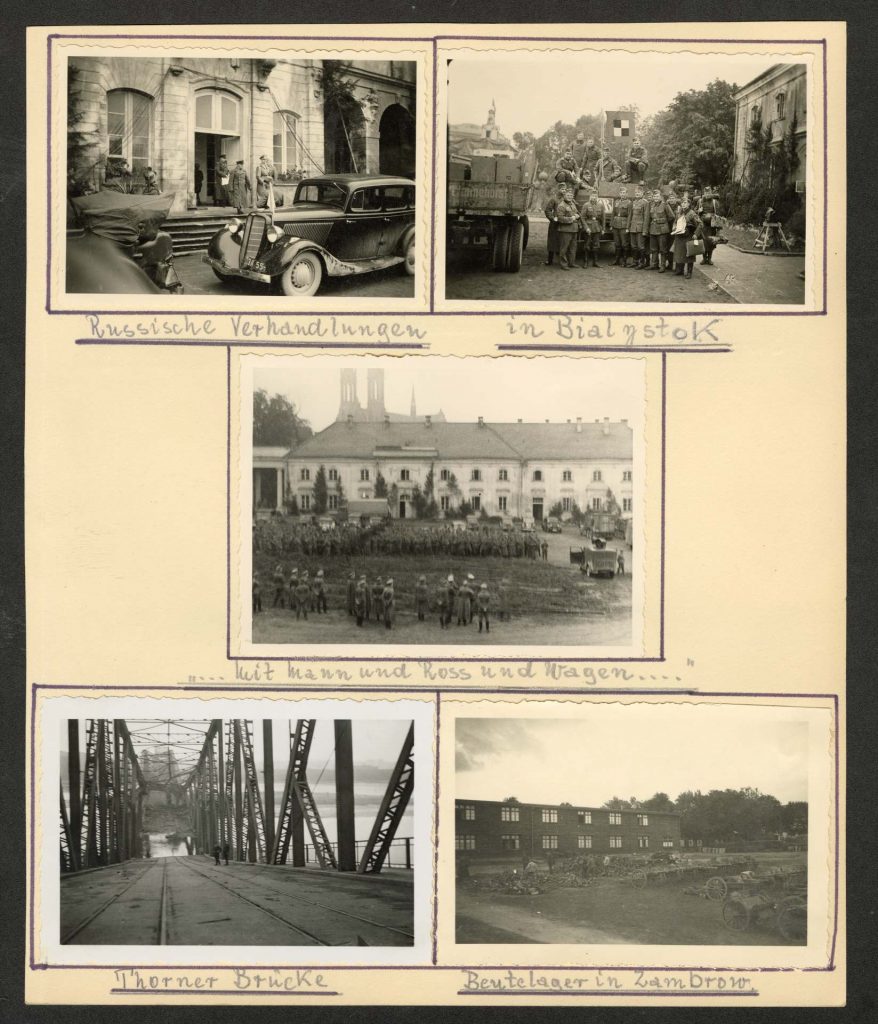

Like every meeting in the series entitled “The Spirit of Sybir”, also the last conversation took place against the background of a showcase with a specially selected exhibit. In the evening of March 22, it was a selection of photos from the collection of the Sybir Memorial Museum, depicting meetings and talks between the representatives of the Soviet Union and the Third Reich in September 1939 in Białystok and Zambrów. — The outbreak of World War II was the result of cooperation between two totalitarian regimes — reminded Piotr Popławski, PhD, from the Sybir Memorial Museum, who welcomed the guests.

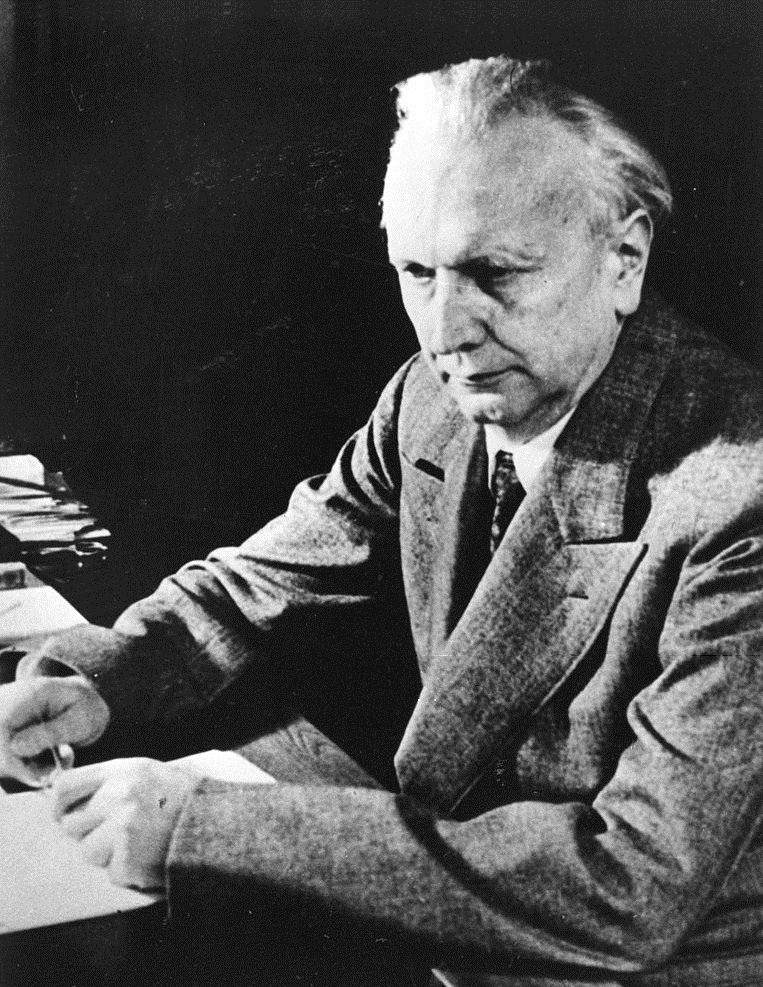

Basil Kerski, political scientist and essayist, manager of culture, who has been the director of the European Solidarity Center in Gdańsk since 2011, did not hide his surprise:

— “I didn’t know these photos would accompany us. It makes me think what a falsification of history on Putin’s part to announce that the invasion in Ukraine is a fight against fascism. Of course, it is worth recalling that Hitler’s greatest successes, including the invasion of the West, were possible thanks to very active cooperation — for example, supplies from the Soviet Union. The paradox of history: Hitler judged himself, and Stalin became a co-author of the new post-war order that shaped our fate so much. I’m saying this as the director of the European Solidarity Center — “Solidarity” are people who fought to change this order. It seemed to all of us that we had succeeded — and today we are witnessing the relevance of this story, we are still fighting to replace this Stalinist order with a democratic order… — said Professor Czyżewski’s interlocutor.

The threads of cooperation between Germany and Russia, as well as the differences between them, were the leitmotif of the whole conversation. In the context of Russia and the Russians, references to the current political situation and the war in Ukraine could not be missing.

— Today, the topic is also the confrontation with the totalitarian and fascist heritage of Russia. The stage of Putin is a transformation within the authoritarian system. I don’t know if 20 years ago I would have called Putin’s system fascist. Today, without ideology, to put it coldly, I would call it fascist: open border revisionism and war against civilians, deportations. It is also the war against the citizens of the Federation who have tried to resist in recent years, murdering these people. Unexpected development for us — without idealizing Gorbachev, Yeltsin, undemocratic Russia, which was looking for some distance, opening archives, started talking about Katyn and the Gulag, but now there has been a radical direction towards fascist Russia.

Reflecting on how Germans struggled with the legacy of fascism after the war, Basil Kerski posed the question: — Who do we talk about when we talk about Germans? If we talk about the post-war history of Germany, we have several dimensions of discourse.

— We have Germany controlled by democratic states that were interested in building democracy and also used their citizens of German origin for this purpose — they urged German emigrants, anti-fascists, to return and build democracy. For me, such a symbolic figure is Willy Brandt, the chancellor of Germany. His election in 1969 was a sensation: an emigrant, a former Norwegian citizen. We also have a gigantic emigration of intellectuals, not only German Jews, who managed to leave before 1939 and save their lives, after the war they co-create the world discourse, for example Hanna Arendt or a historian, Golo Mann.

— And we have a very interesting situation in the Stalinist, then communist part of Germany, where there is supposedly a distance to German fascism. The only historical truth, which is little known in Poland, is that it’s not like Hitler or the NSDAP was elected by a majority. Hitler, who came to power in 1933, was given a chance because he was seen as weak. The very conservative, democratically critical and even anti-democratic forces in the military thought they could integrate Hitler. But he understood his 5 minutes and carried out a total coup d’état using violence, building the first concentration camps. The role of the Communist Party of Germany, supported by Stalin, was disastrous. German communists were interested in the collapse of democracy, they fought the forces of the political center, i.e. the anti-communist movement of workers, Christian Democrats, democratic Catholics and liberals — said Kerski.

— There are moments we miss. Mixed systems cannot be trusted, because they open up an opportunity for totalitarianisms — he stressed.

– Against the backdrop of Germany’s mistakes and disastrous policy in recent years, we fall into such an image of a cohesive state and society, we do not see that this conflict of communism and fascism is inscribed in the history of German democracy — democracy that existed in the 1920s. If we are talking about Russia today and we want compare with Germany — Russia has no democratic traditions, it has failed to create them — he concluded.

The interviewer, Krzysztof Czyżewski, the creator of the Borderland Centre, referred to the German psychiatrist and existentialist philosopher, Karl Jaspers.

“Jaspers was an opponent of the Third Reich” — said Basil Kerski. — He published the book immediately after the war. His thought at that time had no influence, but from today’s perspective it is a universal view of the problem of experiencing totalitarianism. Jaspers, a strong critic of Stalin and Hitler — for him Stalin is not someone who liberates Europe — offers us a view of history that opens us to the future, but does not leave the past behind us. He sees four dimensions of guilt, I would say responsibility.

— The first is criminal — the ECS director enumerated. — This is the time when the Allies manage to introduce into the culture of the world the form of an international tribunal that judges not only criminals, but the entire system. But Jaspers forms perspectives that were unpopular then and are unpopular today. It’s about political responsibility. i.e. he is against the collective guilt of the Germans, because he sees a chance to escape — it is easy to judge nations because you can clear yourself of responsibility.

— But this political responsibility — Kerski explained — is a question of whether we as citizens sensed this moment or whether we reacted appropriately as opponents. But then Jaspers, a victim of the Third Reich, inscribes himself in this experience, speaking of moral and metaphysical guilt. Moral — whether I, as a human being, have been sufficiently involved, for example, in the protection of life.

— There is a testimony of Władysław Bartoszewski who, in the late 1980s, when asked about his heroism as a witness, a member of Żegota (The Council to Aid Jews) and an Auschwitz prisoner, said that someone who survived the Holocaust witnessed the murder of Jews, did not feel any satisfaction that he had survived, that he worked in Żegota (The Council to Aid Jews). He doesn’t feel on any bright side, but he feels deep guilt that so few people have been saved. This is the moral dimension. And metaphysical — a very important topic for our culture, Polish. I am reminded of Miłosz, Błoński. It was a text written for the Germans, but Jaspers created a perspective that draws the whole world in. For example, this metaphysical guilt of a Christian standing in front of the ghetto in Warsaw or Białystok is something that may also apply to the victims — said the guest of the Sybir Memorial Museum.

“Jaspers’s thinking was revealed for the first time in the form of public life… in Warsaw, in December 1970.” — Kerski noted. — Many people wondered why Willy Brandt was kneeling in front of the Monument to the Ghetto Heroes, after all, he was in exile at the time, fighting fascism from the very beginning. This sense of political responsibility, as the head of the government of a state in which, however, the majority of citizens supported… But also the sense of this moral and metaphysical responsibility…

— Few people know, probably Marek Edelman said during his lifetime, that Willy Brandt, as a young man, with falsified papers, found himself in Warsaw in 1937 and attended a congress of young Bundists, Jewish-Polish socialists. Marek Edelman claimed that he met Brandt then. In short, Brandt knew pre-war Warsaw and met those people whom we commemorate in this monument…

We encourage you to get familiar with the recording of the entire meeting: